Introduction: The Paradox of the Cross

The central message of the early Church—that its savior was a man executed by crucifixion—was, in the words of the Apostle Paul, a “stumbling block” to Jews and “foolishness” to Gentiles (1 Corinthians 1:23). For this reason, the earliest followers of Jesus were extremely reticent to use the cross as a devotional image. To do so would have been to openly embrace a symbol of ultimate worldly failure and disgrace. This essay will trace the evolution of the cross, examining how this emblem of ignominy was transformed into the primary symbol of a global faith. It will explore the coded visual language of the early, persecuted Church; the pivotal historical moment that recast the cross as an imperial standard; and the subsequent theological and artistic developments that shaped its meaning, from a trophy of divine victory to a focus of profound human suffering.

The Scandal of the Cross: Why Early Christians Hesitated

The profound lack of devotional cross imagery in the first three centuries is not evidence that the crucifixion was unimportant to early Christians. On the contrary, this artistic silence is the strongest possible evidence of the symbol’s overwhelmingly negative connotation in the Roman world. The scandal of the cross was so potent that it could only be approached through coded language, theological argument, or, by outsiders, in the form of mockery. The pre-existing, horrific meaning of the symbol prevented its use in art.

The Tree of Shame

In the Roman Empire, crucifixion was a state-sanctioned spectacle of torture and humiliation. It was a punishment reserved almost exclusively for the lowest echelons of society: slaves, violent criminals, and rebellious foreigners. For a Roman citizen to be crucified was an almost unthinkable outrage. The Roman orator Cicero famously described the cross as the arbor infelix—the unlucky or shameful tree—and declared that “the very word cross should be far removed not only from the person of a Roman citizen but from his thoughts, his eyes, his ears.”

The process was designed for maximum public degradation. Victims were often scourged, forced to carry their own crossbeam, and crucified naked in a public place, where they would die a slow, agonizing death over several days from asphyxiation and exhaustion. This brutal reality meant that the cross was universally understood as a symbol of criminality, shame, and the absolute power of the Roman state to crush its enemies.

Foolishness to the Gentiles

Against this cultural backdrop, the central Christian proclamation—that a man executed in this most degrading manner was in fact the divine Son of God and Savior of the world—was intellectually and culturally absurd. The mockery Jesus received from onlookers as he hung on the cross—“save yourself, and come down from the cross!” (Mark 15:30)—reflected the logical Greco-Roman perspective: a true divine being would possess the power to avert such a powerless and shameful fate. To worship a crucified man was, from the outside, to worship failure and weakness.

Early Traces and Mockery

Despite the Christian community’s reluctance to depict the cross, its centrality to their faith was known to outsiders, who often used it as a point of ridicule.

Pagan Accusations: In the 2nd and 3rd centuries, pagan critics derisively referred to Christians as crucis religiosi, or “adorers of the gibbet.” This accusation, recorded by Christian apologists like Tertullian, demonstrates that the link between Christians and the cross was firmly established in the public mind long before Christians themselves used it as a public symbol.

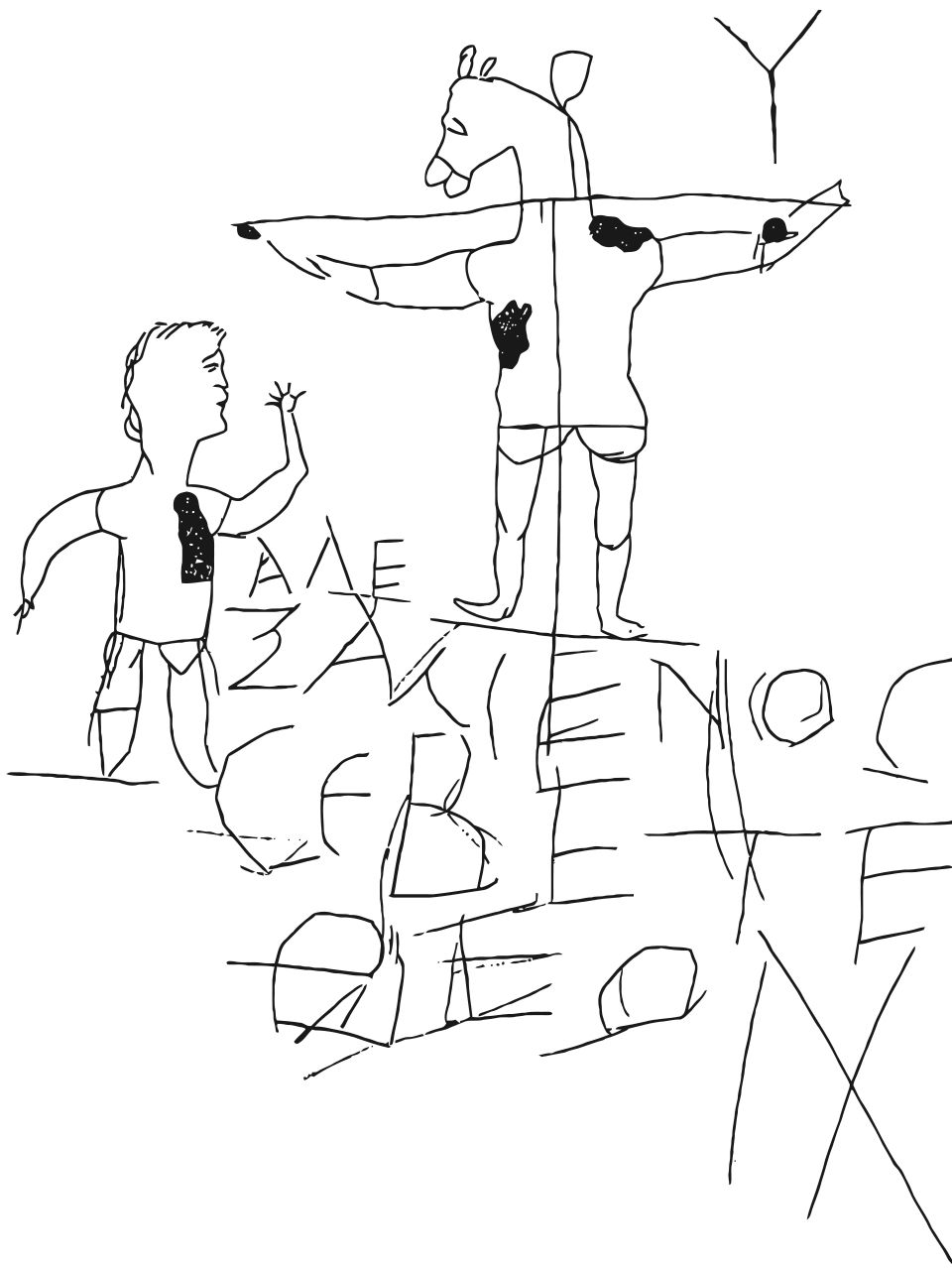

The Alexamenos Graffito: The earliest known pictorial representation of the crucifixion is not a Christian work of devotion but a piece of pagan mockery. Discovered on a wall in the imperial training school for slaves on Rome’s Palatine Hill and dated to around 200 AD, the crude etching depicts a figure with the head of a donkey on a cross. Another figure stands below with one hand raised in a gesture of worship. The Greek inscription reads, “Alexamenos worships his god.” This satirical image is invaluable historical evidence. It confirms that the crucifixion of Jesus was the core of Christian belief and that this belief was so strange to outsiders that it invited ridicule, possibly drawing on accusations that Christians, like Jews, engaged in donkey-worship.

Disguised Crosses: The need to express the central truth of the faith while avoiding its shameful depiction led to the use of disguised forms. As we will see in the next section, the anchor was a primary example. Another was the staurogram, a ligature of the Greek letters Tau (T) and Rho (P) to form the symbol ⳨. Found in very early New Testament manuscripts to abbreviate the Greek word for cross, stauros, the staurogram visually resembles a human figure hanging on a cross, thus serving as a subtle, coded reference to the crucifixion.

By embracing the foolishness of the cross, early Christians were making a radical, counter-cultural statement. They were defining themselves and their values in direct opposition to the Roman ideals of honor, power, and status. Their central story was not one of worldly triumph, but of divine power revealed through ultimate worldly failure. This made the cross a powerful litmus test of faith, a symbol that differentiated their message from all others.

A World of Coded Symbols (c. 100–312 AD)

In the first three centuries, before Christianity was legalized by the Emperor Constantine in 313 AD, the faith existed as a minority—and often persecuted—sect within the Roman Empire. This context of potential danger necessitated a symbolic, rather than explicit, visual language. The most significant body of evidence from this pre-Constantinian period comes from the catacombs of Rome—vast, commercially operated underground burial sites used by Christians and pagans alike. The art found on the walls of these tomb-chambers was not merely decorative; it served a dual purpose of instructing a largely illiterate community in the tenets of the faith and reinforcing the central message of salvation and deliverance from death for the grieving.

In this environment, where the cross itself was too scandalous to depict, a rich lexicon of other symbols flourished. The early Christian community developed a sophisticated visual shorthand, drawing on biblical narratives, Greek wordplay, and even the surrounding pagan culture to create symbols that were rich in meaning for the initiated but innocuous to outsiders.

The Ichthys (Fish)

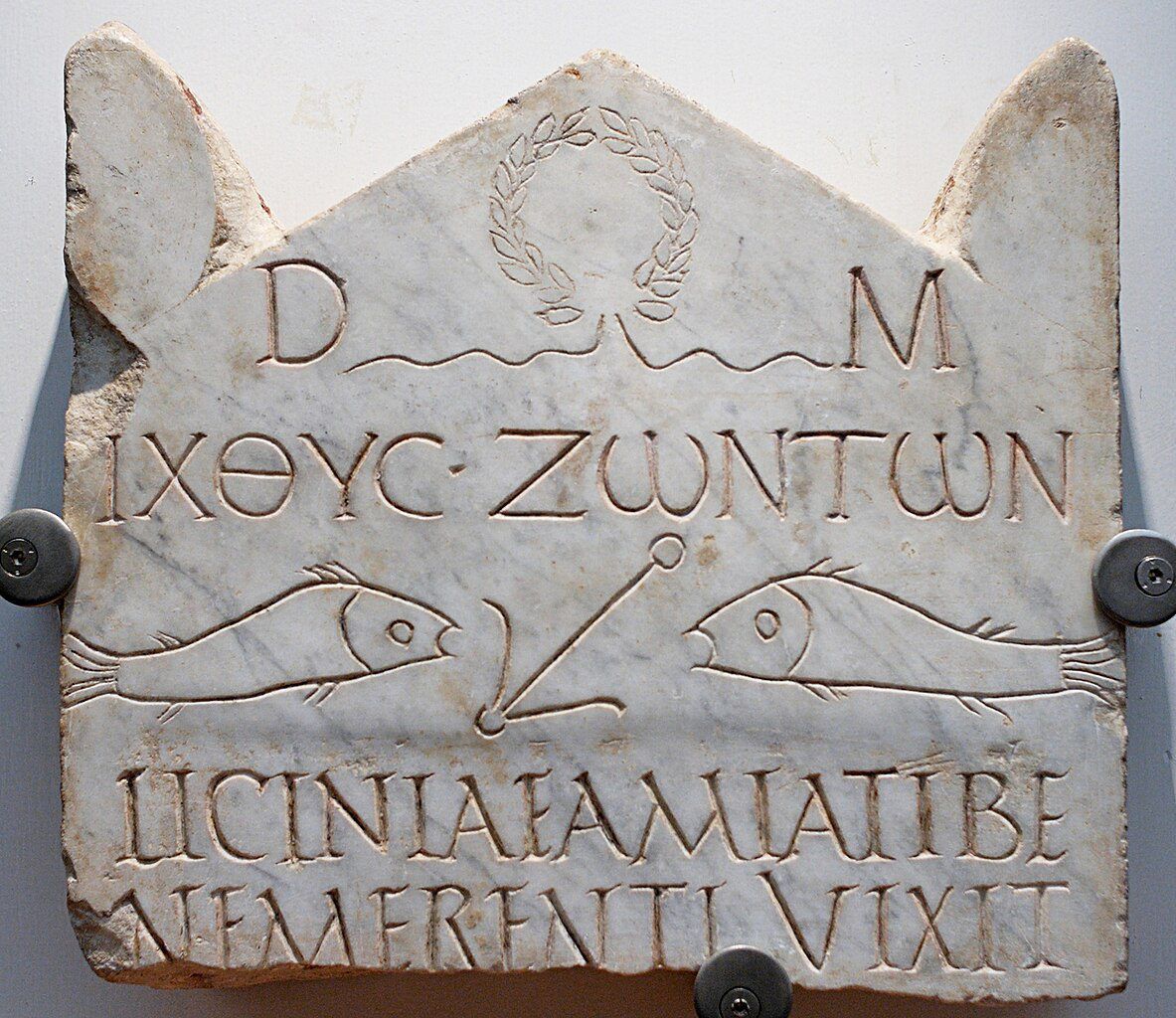

Arguably the most important and widespread early Christian symbol was the fish. The power of the Ichthys lay in its multiple layers of theological and practical significance. Its primary importance came from a Greek acrostic: the letters of the word for fish, IXΘΥΣ (Ichthys), formed the initial letters of the phrase Iesous Christos, Theou Yios, Soter, which translates to Jesus Christ, God’s Son, Savior. A simple drawing of a fish was therefore a complete and profound confession of faith.

During times of persecution, this symbol could be used as a clandestine sign of identification. According to tradition, one person might draw a single arc in the dirt, and if the other was a fellow Christian, they would complete the fish by drawing the opposing arc. The symbol was also deeply resonant with Gospel narratives, evoking the miraculous feeding of the five thousand, Christ’s call to the apostles to become fishers of men, and the post-resurrection meal of fish he shared with his disciples. In catacomb art, the fish, often depicted alongside bread, became a clear symbol for the Eucharist. The early Church Father Tertullian (c. 160–220 AD) extended the metaphor to baptism, writing: “we, little fishes, after the image of our Ichthys, Jesus Christ, are born in the water.”

The Anchor (Crux Dissimulata)

Another prevalent symbol was the anchor, which drew its meaning directly from the Epistle to the Hebrews 6:19: “We have this hope, a sure and steadfast anchor of the soul.” It represented safety and steadfast hope in salvation. The true genius of the anchor for early Christians, however, was its form. With its top ring and horizontal crossbar, it bore a strong resemblance to a cross. This allowed it to function as a crux dissimulata, or disguised cross—a symbol that was cruciform in shape but could be plausibly interpreted as a simple nautical device by outsiders. This visual ambiguity was a crucial feature for a community that needed to hide in plain sight. Inscriptions in the catacombs from as early as the first century feature the anchor, often alongside inscriptions of peace like pax tecum (peace be with you), expressing the hope of eternal life. Some depictions combine the anchor with fish, creating a powerful symbolic image of Christ’s saving work on the cross.

The Good Shepherd

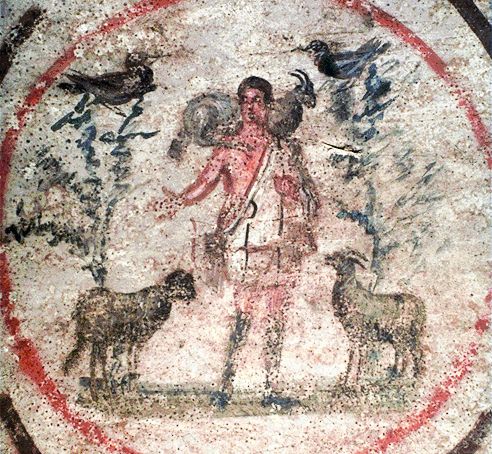

The most common personified image of Jesus in the pre-Constantinian era was that of the Good Shepherd. This motif demonstrates a key strategy of early Christian art: the shrewd re-appropriation of familiar cultural images. Artists took the well-known Greco-Roman figure of Hermes Kriophoros (“the ram-bearer”)—a benevolent pagan deity carrying a ram on his shoulders—and imbued it with a new, Christian meaning based on the parables of Jesus in the Gospel of John and Psalm 23. This act of cultural translation allowed Christians to express a core theological concept—Christ as the rescuer of the lost soul—using a visual language that was already familiar and non-threatening to the surrounding Roman culture. The choice of this image, along with other Old Testament scenes of divine rescue like Jonah and the whale or Daniel in the lion’s den, reveals the primary concern of catacomb art. The focus was not on creating a historical biography of Jesus’s life, but on communicating the central theological promise of salvation and deliverance from death, a message of profound comfort in a funerary context.

A Lexicon of Other Early Symbols

The visual environment of the early Church was rich with other symbols that conveyed key aspects of the faith.

Chi-Rho (☧): A monogram formed by superimposing the first two Greek letters of the word Christ (XPIΣTOΣ), Chi (X) and Rho (P). It was one of the earliest Christograms, used as a secret sign long before it was famously adopted by Constantine.

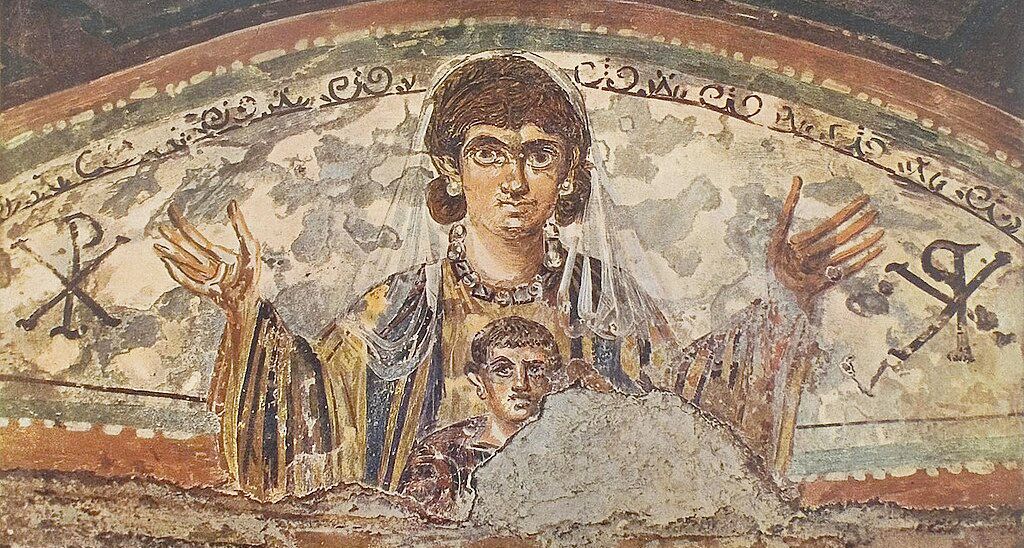

Orant Figure: A standing figure, typically female, with arms outstretched in a posture of prayer. This common image symbolized the soul of the deceased in paradise, at peace and in communion with God.

Dove: Often depicted with an olive branch, the dove symbolized peace, the Holy Spirit, and deliverance, directly referencing the story of Noah and the Ark.

Peacock: A symbol of immortality and resurrection, stemming from the ancient belief that the peacock’s flesh did not decay after death.

Symbol | Representation | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

Ichthys | A simple outline of a fish, formed by two intersecting arcs. | Acrostic Creed: ΙΧΘΥΣ for “Jesus Christ, God’s Son, Savior.” Represents the Eucharist, Baptism, and Gospel stories. |

Anchor | A nautical anchor, often with a ring at the top and a crossbar. | Hope & Security: Based on Hebrews 6:19. Its shape served as a hidden representation of the cross. |

Good Shepherd | A youthful figure carrying a sheep or lamb on his shoulders. | Represents Jesus saving the lost soul. Adopted from the pagan image of Hermes Kriophoros. |

Chi-Rho (☧) | Superimposed Greek letters Chi (X) and Rho (P). | Monogram of Christ: An abbreviation for XPIΣTOΣ. Later became an imperial symbol under Constantine. |

Orant | A figure with arms raised in prayer. | Piety & the Soul in Heaven: Represents the soul of the deceased in paradise, in a state of prayer. |

The Constantinian Shift: From Ignominy to Imperial Emblem (c. 312–337 AD)

The status of the cross was irrevocably altered by one of the most pivotal events in Western history: the rise of the Roman Emperor Constantine. In a remarkably short period, the cross was transformed from a symbol of state punishment into the emblem of imperial power, a complete semiotic inversion that would shape the future of Christianity and its primary symbol.

The Vision at the Milvian Bridge

In 312 AD, the Roman Empire was fractured by civil war. Constantine was one of several contenders for the throne, preparing to face his rival Maxentius at the Milvian Bridge, a key entry point to Rome. According to the historian Eusebius, who received the account from the emperor himself, on the eve of the battle, Constantine and his army saw a miraculous sign in the sky: a cross of light superimposed over the sun, accompanied by the Greek words Ἐν Τούτῳ Νίκα—“In this, conquer.” The Latin version of the phrase is more famous: In hoc signo vinces—“By this sign you will conquer.” That night, Constantine dreamt that Christ appeared to him, commanding him to make a likeness of the sign and use it as a safeguard in battle.

The Cross as Imperial Standard

Constantine obeyed. He ordered his soldiers to paint the Christian symbol—specifically the Chi-Rho monogram—on their shields. His subsequent and decisive victory over Maxentius was attributed to the power of this sign and the Christian God. This event provided divine sanction for his military campaign and his claim to power. In 313 AD, Constantine and his co-emperor Licinius issued the Edict of Milan, which granted religious toleration throughout the empire and effectively ended the persecution of Christians.

The symbol of Christ, once associated with executed rebels, now became the official military standard of the Roman army, known as the Labarum. This standard, a long spear with a transverse bar and a banner, was topped with the Chi-Rho symbol. This act dramatically reversed the cross’s meaning. The instrument used by the state to execute its enemies was now the emblem under which the state’s army marched to victory. Christograms and, eventually, crosses began to appear on imperial coins and soldiers’ helmets, a powerful form of public propaganda that cemented the new alliance between the Church and the Roman Empire.

The Invention of the True Cross

The cross’s new status was further solidified by the actions of Constantine’s mother, the Empress Helena. Around 326–328 AD, she undertook a royal pilgrimage to the Holy Land to identify and preserve sacred sites. According to later accounts by historians like Rufinus and Socrates Scholasticus, Helena ordered the excavation of the site of Christ’s crucifixion in Jerusalem, which had been covered over by a pagan temple to Venus. During the excavation, three crosses were unearthed. To identify which was the True Cross of Christ, the Bishop of Jerusalem, Macarius, had a deathly ill woman touch each of the three crosses. Upon touching the third, she was miraculously healed, thus identifying the authentic relic.

This discovery, whether historical or legendary, marked a significant shift from the conceptual to the material. Commemorated today in the feast of the Exaltation of the Cross on September 14, this event meant the cross was no longer merely an idea or a disguised shape. It was now a physical object that could be seen, touched, divided, and venerated. Helena had a portion of the cross sent to Constantine in Constantinople, while the rest remained in Jerusalem, housed in the new Church of the Holy Sepulchre built by Constantine on the site. Fragments of the True Cross were soon distributed throughout the empire, becoming the most precious relics in Christendom. This materialization of faith fueled the rise of pilgrimage, created a powerful economy of relics, and gave the cross a tangible, miraculous presence in churches far and wide. The imperial patronage of Constantine legitimized the relic, and in turn, the sacred power of the relic legitimized the new Christian empire.

The Iconography of Victory: The Cross in the Post-Constantinian Era

The profound theological and political changes of the Constantinian era gave rise to a new artistic language for the cross. For several centuries, Christian art and devotion centered on the victory of Christ over sin and death, and realistic portrayals of his suffering were deliberately avoided. The art of this period is a direct reflection of an imperial theology that emphasized power, triumph, and divine authority.

The Crux Gemmata (The Jeweled Cross)

The first prominent artistic representations of the cross to appear in the 4th and 5th centuries were not depictions of a gruesome execution, but of a glorious, triumphant trophy: the crux gemmata, or jeweled cross. Found in the magnificent mosaics of churches in Rome and Ravenna, such as the apse of Santa Pudenziana (c. 400 AD), this image is symbolic. The cross is rendered in gold and lavishly studded with gems, signifying Christ’s kingship and his victory over death. It is not an instrument of shame but a victor’s standard.

The symbolism of the crux gemmata was rich and multi-layered. It was often depicted standing on a hill, representing Golgotha, with the city of Jerusalem in the background, symbolizing the heavenly New Jerusalem. The jeweled cross was also explicitly linked to the Tree of Life from the Garden of Eden, now restored to humanity through Christ’s sacrifice. In some depictions, leafy branches or vines sprout from its corners, and the four rivers of paradise flow from its base, representing the four Gospels spreading to the corners of the world.

Christus Triumphans (The Triumphant Christ)

When the figure of Christ began to be depicted on the cross in the 5th and 6th centuries, forming the first crucifixes, the representation was that of the Christus Triumphans, or Triumphant Christ. This iconography is a powerful theological statement about the nature of Christ.

- Characteristics: In the Christus Triumphans style, Christ is shown alive and victorious. His eyes are wide open, his arms are extended straight, and his body is erect and strong, showing no signs of pain or death. He is not a suffering victim but a divine king reigning from the cross as if it were his throne. Often, he wears a long priestly robe (collobium) or a royal crown, rather than a loincloth and a crown of thorns.

- Early Examples: The earliest known narrative depiction of the crucifixion, a small ivory panel from the early 5th century (c. 420–430 AD), already establishes this triumphant theme. Christ is muscular and impassive, his victory over death emphasized rather than his suffering. On the wooden doors of the Basilica of Santa Sabina in Rome (c. 432 AD), an upper-left panel depicts a similar serene and powerful Christ.

This artistic choice was a visual resolution to the central paradox of Christology: how Christ could be both fully God and fully man. By portraying Christ as impassive and alive on the instrument of his death, the Christus Triumphans image heavily emphasizes his divine nature, which transcends and overcomes the physical suffering of his human nature. In an era of intense theological debates, this art served as a public declaration of Christ’s unconquerable divinity.

The Humanity of Christ: The Evolution to the Suffering Savior

Beginning in the High Middle Ages, a profound shift occurred in Christian spirituality, moving from a focus on Christ’s divine majesty and cosmic victory to an intense, empathetic meditation on his human suffering. This change in devotional culture was driven by new theological ideas and popular religious movements, and it produced a dramatically different artistic representation of the cross.

Theological Underpinnings of a New Perspective

Several key developments prompted this shift:

- Anselm’s Satisfaction Theory: In the 11th century, St. Anselm of Canterbury proposed his satisfaction theory of atonement. He argued that human sin constituted an infinite offense against God’s honor, creating a debt that finite humans could never repay. Only a being who was both God (to have infinite merit) and man (to represent humanity) could pay this debt. Christ’s willing suffering and death on the cross was this perfect act of satisfaction. While Anselm’s theory focused on honor rather than punishment, it drew intense theological focus to the necessity and mechanics of Christ’s suffering, making the Passion a central subject of intellectual inquiry.

- Franciscan Affective Piety: In the 13th century, the Franciscan movement, founded by St. Francis of Assisi, championed a new form of affective piety—an emotional, personal, and empathetic devotion to the humanity of Christ. Francis had a deep, personal connection to the Passion, famously receiving the stigmata (the wounds of Christ) on his own body. This new spirituality encouraged believers to imaginatively and emotionally participate in Christ’s suffering, to feel compassion for his pain, and to see in the cross the ultimate expression of God’s humble love.

This transition from a corporate, imperial faith to a more personal and mystical one created the demand for an art that could serve as a focus for this new, empathetic devotion. The art began to mirror a fundamental change in how people prayed and related to God.

Christus Patiens (The Suffering Christ)

This new devotional climate gave rise to a new iconography: the Christus Patiens, or Suffering Christ. In stark contrast to the triumphant king, this style depicted the brutal reality of the crucifixion. The Christus Patiens shows a dead or dying Christ. His eyes are closed, his head slumps onto his shoulder, and his body sags, contorted in agony under its own weight. His humanity is emphasized through the graphic depiction of his wounds, with blood streaming from his hands, feet, and side. The goal of this art was to evoke a powerful emotional response—pity, sorrow, gratitude, and compassion—from the viewer, drawing them into a deeper personal relationship with the suffering savior.

The Reformation and the Cross

The 16th-century Protestant Reformation introduced another major development, turning the visual representation of the cross into a point of explicit theological contention between Christian groups.

- Martin Luther’s Theologia Crucis: The reformer Martin Luther coined the term theologia crucis (theology of the cross). He argued that true knowledge of God is found not in human reason or glorious deeds (theologia gloriae), but paradoxically in the suffering, shame, and foolishness of the cross. For Luther, the cross reveals a God who works in ways hidden and contrary to human expectations.

- The Empty Cross: While Luther himself retained the crucifix, other reformers, notably John Calvin, rejected all religious images, including the crucifix, as graven images forbidden by the Second Commandment. This led to the preference in many Protestant traditions for an empty cross. The theological rationale that developed for this choice is that the empty cross powerfully symbolizes the Resurrection: Christ has conquered death and is no longer on the cross. This choice is not merely aesthetic but a doctrinal statement. For Catholics, the crucifix makes present the singular, timeless sacrifice of Christ, which is central to the Mass. For many Protestants, the empty cross makes a definitive statement about the completed work of Christ and the triumph of his resurrection. The symbol that once unified a persecuted minority now became a key visual differentiator between the major branches of Western Christianity.

The Modern Cross: Ubiquity, Identity, and Controversy

In the modern era, the journey of the cross has culminated in its status as the primary, instantly recognizable symbol of Christianity worldwide. Its display on church buildings, in homes, schools, and public spaces, and as personal jewelry serves as a constant, visible attestation of faith and a marker of Christian identity. However, this ubiquity has also led to a fragmentation of its meaning and new cultural controversies.

The Crucifix vs. the Empty Cross: The Divide Today

The theological divide that emerged during the Reformation continues to define the use of the cross in different Christian traditions.

- Catholic, Orthodox, and High-Church Traditions (Anglican, Lutheran): These traditions continue to prominently use the crucifix. Catholic liturgy, for instance, requires a crucifix to be present during the Mass, as the service is understood to make the sacrifice of Calvary present to the faithful. The crucifix serves as a powerful reminder of the price of redemption and the depth of Christ’s love. This emphasis on the crucifix does not, however, exclude the use of the empty cross, which is also found in many Catholic churches and communities.

- Protestant Traditions: Many Protestant denominations, particularly those from the Reformed, Baptist, and Methodist traditions, strongly prefer the empty cross. The primary theological emphasis is on the resurrection and the victory over death. The common refrain is “My Savior is not on the cross; he is risen.” The empty cross is seen as a symbol of the completed work of salvation and the hope of new life.

The Cross as a Contested Public Symbol

In increasingly pluralistic and secular societies, the public display of the cross has become a source of cultural and legal conflict.

- Public Display: The placement of large crosses on public land, in government buildings, or in state-funded schools often sparks legal challenges regarding the separation of church and state. What one group sees as a symbol of heritage and hope, another sees as an inappropriate state endorsement of a particular religion.

- Cultural Misappropriation: The meaning of the cross has been distorted and misappropriated by various groups. Most notoriously, the Ku Klux Klan adopted the fiery cross as a symbol of terror and racial hatred, turning an emblem of salvation into one of intimidation and violence.

- Theological Critiques: Some modern theologians, particularly from feminist and liberationist perspectives, have critiqued traditional interpretations of the cross. They argue that an overemphasis on passive suffering has been used historically to justify and glorify the oppression of marginalized groups, encouraging meek submission to abuse rather than resistance to injustice.

The very ubiquity of the cross presents a modern paradox. On one hand, its meaning can be trivialized, reduced to a mere fashion accessory or cultural artifact stripped of its profound theological weight. On the other hand, its public display can become highly polarized, functioning as a partisan emblem in cultural conflicts.

Conclusion: An Enduring Symbol

The evolution of the cross in Christian iconography is a remarkable journey from an object of ultimate shame to the preeminent symbol of a global faith. For nearly three hundred years, it was a sign so scandalous that it was hidden in coded symbols like the fish and the anchor. The imperial patronage of Constantine dramatically reversed its meaning, transforming it into an emblem of victory and divine authority, visually expressed in the glorious crux gemmata and the impassive Christus Triumphans.

A subsequent shift in piety during the Middle Ages, driven by new theological frameworks and a desire for personal, empathetic faith, brought forth the suffering Christ, the Christus Patiens, an image designed to evoke compassion and devotion. The Reformation further fractured the symbol’s interpretation, creating the enduring visual divide between the Catholic crucifix and the Protestant empty cross. Today, the cross is at once ubiquitous and contested, a symbol of personal identity, cultural heritage, and sometimes, public controversy.

This continuous evolution reveals a profound truth: the way a community depicts the cross exposes its theological priorities. The art of the cross is a mirror reflecting the Church’s understanding of God, salvation, and its own place in the world at any given moment in history. Whether seen as a hidden hope, an imperial trophy, a companion in suffering, or a sign of resurrection, the cross remains a potent and enduring symbol precisely because it embodies the central, challenging paradoxes of the Christian faith: life through death, strength through weakness, and glory through suffering.