Setting up the Christmas crèche in our homes helps us to relive the history of what took place in Bethlehem. Naturally, the Gospels remain our source for understanding and reflecting on that event. At the same time, its portrayal in the crèche helps us to imagine the scene. It touches our hearts and makes us enter into salvation history as contemporaries of an event that is living and real in a broad gamut of historical and cultural contexts.

—Pope Francis, Admirabile signum, §3

Christmas is the happiest moment of the year for many. In fact, countless beautiful childhood memories of mine are related to Christmas. I fondly remember our trips as a family during Christmas breaks. Decorating our Christmas tree also proved so much fun.

Another important memory of mine has to do with the first Nativity scene my parents bought for our home. Vacations and Christmas trees were splendid, yet it’s hard for me to think of a Christmas-related tradition that centers us on the mystery of God-made-man better than the Nativity scene. By meditating on the figures of the crèche, we shall better appreciate the meaning of Christmas.

1. The Shepherds and the Magi

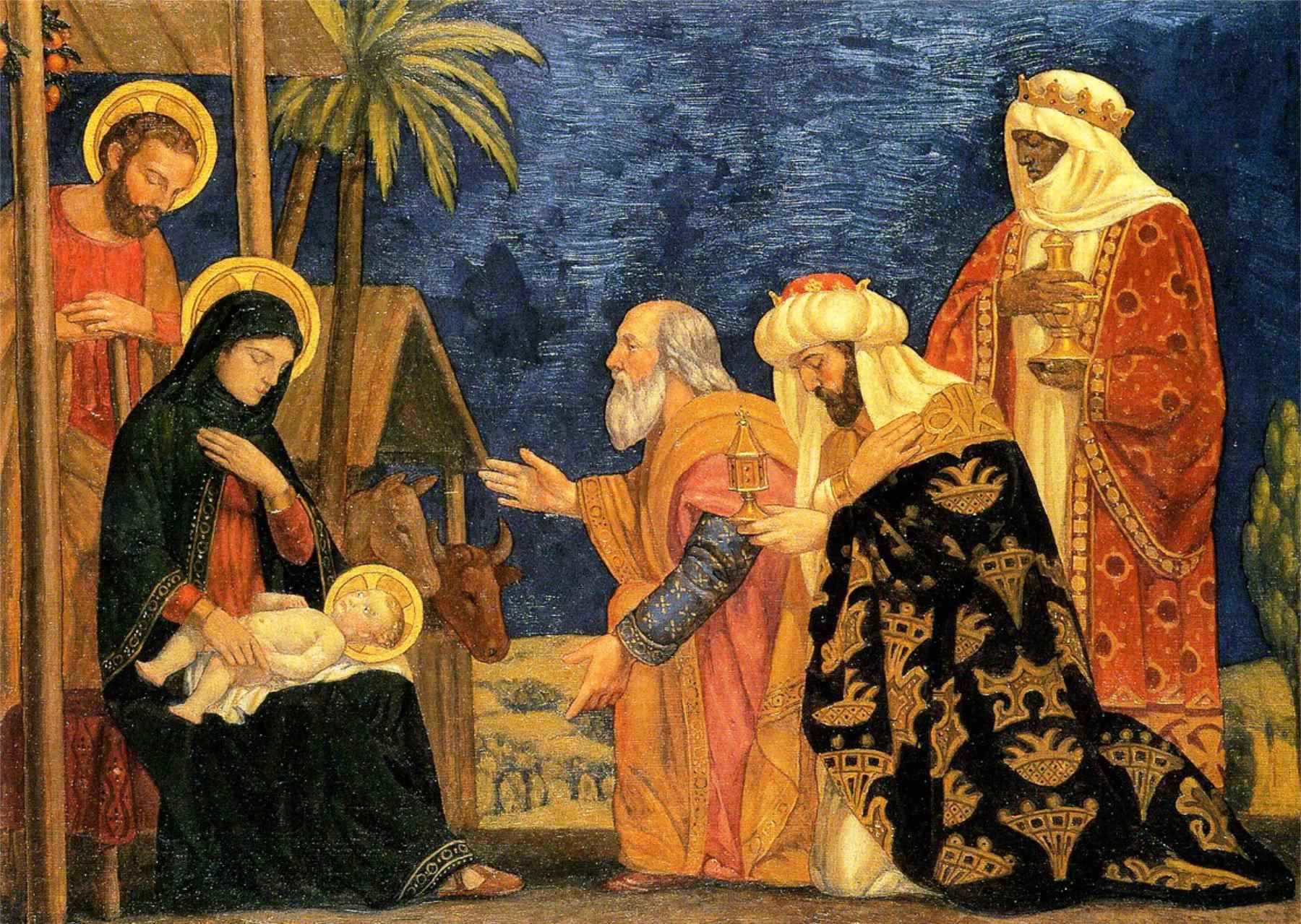

On entering the house, [the wise men] saw the child with Mary his mother; and they knelt down and paid him homage. Then, opening their treasure chests, they offered him gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh.

—Matthew 2:11

[The shepherds] went with haste and found Mary and Joseph, and the child lying in the manger. When they saw this, they made known what had been told them about this child.

—Luke 2:16–17

Let’s begin our reflection by looking at the first to arrive at the crèche: the shepherds and the magi. Their presence is so traditional we risk forgetting to ask the most important question: why them? Why these two specific groups, from opposite ends of the social, religious, and economic spectrum?

In their joint presence, we see a proclamation of the universality of the new covenant, but also a beautiful illustration of two distinct liturgical mysteries.

The shepherds were the first to receive the angelic news. In ancient Israel, shepherds were often marginalized, seen as rough, unclean, and unreliable. Yet, they were also the symbolic remnant of Israel, the anawim, the poor and humble who trusted completely in God. Their arrival represents the intimate coming of the Messiah to his own people. As the liturgist Pius Parsch noted, their presence makes Christmas the "intimate family feast," attended by the Holy Family and their closest neighbors.

The Magi, in contrast, were the ultimate "outsiders". They were Gentiles from a distant land, seekers who read the signs of creation. Their journey, guided by a star, represents all of humanity’s rational and philosophical searching for the divine. Their quest shows that all sincere pursuit of truth, whether through reason or revelation, ultimately leads to the same destination: Jesus Christ. This journey represents the universal manifestation—the Epiphany—of this King to all the nations of the world.

Thus, in one scene, the "dividing wall" is torn down. The faithful remnant of Israel (the shepherds) and the seeking nations (the Magi) kneel side-by-side, uniting the intimate mystery of Christmas with the universal mystery of Epiphany. But what unites them? What is their entrance ticket to the Nativity scene?

In one of his talks, Fulton Sheen wittily remarks that shepherds are those who know they know nothing. Magi, on the other hand, are those who know they do not know everything. We do not find the know-it-alls, in contrast, at the Nativity scene.

Only the humble are there. Humility. This is the virtue that binds them, and it is the lesson they teach us.

One afternoon back in 2019, I was seated in a bus. I was so thrilled when I heard our tour guide say: “Welcome to Bethlehem!” Our main destination there was the Basilica of the Nativity.

As we approached the Basilica, the first thing that struck me was how low the entrance was. This "Door of Humility" used to be 5.5 meters high. Yet, during the Ottoman Era, it was reduced to about 1.2 meters to prevent people from entering on horseback. So, unless your height is less than 1.2 meters, you must duck your head in order to pass through.

That is what Bethlehem teaches us. To recognize who the baby Jesus is, we have to bow down. Whether we are a simple shepherd or a learned magus, we must dismount the "horse" of our pride. To approach his birthplace, we ought to be humble.

2. The Ox and the Ass

The tradition of setting up Nativity scenes can be traced back to the Christmas Mass celebrated by St. Francis of Assisi at a cave in Greccio, Italy, in 1223. Curiously, prior to the Mass, the saint had directed that an ox and an ass should be present. But the theology he was illustrating was already a thousand years old.

The questions would be: why an ox and an ass? What do they have to do with Christ’s birth? We do not find them in the canonical Gospel accounts of Matthew or Luke.

Their presence comes from a profound theological reading of the prophet Isaiah, who was contrasting the disobedience of Judah with the simple knowledge of animals:

The ox knows its owner, and the ass its master’s crib; but Israel does not know, my people does not understand.

—Isaiah 1:3

This connection was famously explored by the third-century Church Father, Origen of Alexandria. While his Homilies on Luke, the likely source for this specific teaching, survive only in fragments, his powerful allegorical interpretation became central to the Church's tradition.

Origen, applying Isaiah's prophecy to the Nativity, saw the animals as representing the whole of humanity coming to Christ. The ox, a clean animal under the Mosaic Law and a beast of burden, symbolized the people of Israel, bound by the Law. The ass, considered an unclean animal by the same Law, symbolized the pagan nations (the Gentiles).

Thus, their presence at the master's crib is a living prophecy. At the birth of Christ, the "wall of separation" (cf. Ephesians 2:14) is broken down. Both Jew and Gentile kneel together, recognizing their common Lord and finding their nourishment in the Word made flesh.

Furthermore, the animals represent all of non-human creation. They are the humble beasts of burden, a fitting court for a King who chose poverty. Their simple, silent presence reminds us that while humanity was disobedient, the natural world never forgot its Creator and now bows before him.

This tradition starkly contrasts the animals’ simple "knowing" with the people who "do not understand." It forces us to ask: Can we affirm that we know Jesus as the ox knows its owner? Or, at least, do we seek to know him better? If we recognize him as our owner, as our Lord, there is a place for us near his crib.

3. Mary and Joseph

While [Joseph and Mary] were there, the time came for her to deliver her child. And she gave birth to her firstborn son … .

—Luke 2:6–7

Near the baby Jesus stand Mary and Joseph, gazing at God-made-man. Words are incapable of expressing what is before them. They are both silent. Pope Francis writes that:

The birth of a child awakens joy and wonder; it sets before us the great mystery of life. Seeing the bright eyes of a young couple gazing at their newborn child, we can understand the feelings of Mary and Joseph who, as they looked at the Infant Jesus, sensed God’s presence in their lives.

—Pope Francis, Admirabile signum, §8

Yet, the silences of Mary and Joseph are not identical. They are distinct and complementary, modeling for us the two essential poles of the Christian life.

Mary’s silence is receptive and contemplative. She is a discreet figure in the New Testament, speaking only six sentences plus one canticle. Her primary posture is one of profound interiority. As the Gospels tell us, she “treasured up all these things and pondered them in her heart” (Luke 2:19). She is the Theotokos, the God-bearer, who first conceived the Word in her heart through faith before conceiving him in her womb. Her stillness is the rich, fertile ground in which the Word of God can take root. She is the supreme model of the vita contemplativa (the contemplative life).

Joseph’s silence is the silence of action. What about him? He says not a single word in all of Scripture. His is not a silence of pondering, but of doing. Joseph listens to God—in the troubling appearance of an angel, in the urgent warnings of dreams—and he acts immediately, faithfully, and without question. He takes Mary into his home; he flees to Egypt; he returns to Nazareth. He is the vir iustus, the "just man," who embodies the vita activa (the active life), protecting and serving the Word-made-flesh.

Together, they reveal that all true Christian life, whether active or contemplative, must be rooted in a deep, attentive listening to God.

Silence. In this noisy world, silence has become a sign of contradiction, a lost art. Yet silence is priceless. It indicates an openness and readiness to listen—to God and to others. Our society and family would be a much better place if we listen to one another more attentively (yes … put your smartphone away for a moment, will you?). Our silence tells the other person that she matters; that she is worth our time.

In this noisy, indifferent, and superficial world, we can surely benefit from learning from Mary the art of contemplative silence and from Joseph the art of active, obedient silence.

4. The Host of Angels

A host of angels appeared to the shepherds. The Greek word Luke uses for ‘host’ is stratias (στρατιᾶς)—a military term, the root of our word strategy. We read that:

suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heavenly host, praising God and saying, “Glory to God in the highest heaven, and on earth peace among those whom he favors!”

—Luke 2:13–14

This is not a quaint choir; it is the arrival of a heavenly army. But this army does not manifest God’s might through worldly conquest. Their "strategy" is doxology—their weapon is praise.

The first thing this heavenly court does is proclaim, “Glory to God in the highest.” Their appearance reveals that the Nativity is not a small, quiet, earthly event. It is a cosmic and liturgical event. Heaven breaks into earth as the angelic army acclaims its true King, who has taken on flesh.

The content of their proclamation is “peace on earth.” This peace is not the mere pax Romana of the empire, an absence of political conflict. It is the biblical shalom. This peace is the tranquilitas ordinis or "tranquility of order" described by St. Augustine: the right-ordering of all creation that makes a worthy and human existence possible. This external order also has a profound internal dimension. As St. Thomas Aquinas explains, it is both concord with others and interior peace. This interior peace, which Aquinas notes is a fruit of charity, is the "union of the appetites of the one desiring"—a state where all our desires are harmoniously directed toward the good. Ultimately, this peace is the definitive reconciliation between God and humanity, the source of all true order.

The angels announce that this child is that peace. Their presence teaches us that God’s true power is not found in earthly might, but in the self-emptying humility of a baby. This small child, now acclaimed by the heavenly army, is the center of cosmic history, the source of heaven's praise, and the beginning of humanity's true peace.

5. The Baby Jesus

[Mary] gave birth to her firstborn son and wrapped him in bands of cloth, and laid him in a manger, because there was no place for them in the inn.

—Luke 2:7

Finally, our Nativity scene becomes alive when we lay the baby Jesus down on the manger. All the other figures—Mary and Joseph, shepherds and magi, angels and animals—find their single point of focus in him. In him, two central mysteries are revealed.

The first is the mystery of divine humility. Jesus comes in silence, weakness, and total dependence. He does not arrive as a conquering king, but as a helpless baby. And yet, the Church’s liturgy presents us with a profound paradox. The very first antiphon of the First Vespers of Christmas Day does not acclaim the Infant of Bethlehem, but rather the “King of Peace [who] has shown himself in glory: all the peoples desire to see him.”

This is the heart of the mystery: his humility is his exaltation. He comes to heal us from within, able to "sympathize with our weaknesses," since he "has been tested as we are, yet without sin" (Hebrews 4:15). This choice of weakness is the heart of God’s plan, what the Church Fathers called the admirabile commercium, the "wonderful exchange": God became man so that man might be made God. His weakness is, as Joseph Ratzinger explains, strategic: "God comes without weapons, because he does not want to conquer from the outside but to win us over from within and to transform us from within."

The second mystery, which fulfills the first, is the mystery of the Eucharist. We observe that the baby Jesus is laid in a manger (Luke 2:7). A manger is not a cradle; it is a feeding trough for animals. This detail is the key. As St. Augustine remarks: "Laid in a manger, he became our food."

This is no accident. He is born in Bethlehem, which in Hebrew (בֵּית לֶחֶם, Beit Lechem) means "House of Bread."

The child who is born in the House of Bread is laid in a feeding trough because he is the Bread of Life (John 6:35). From the very first moment of his Incarnation, he presents himself as our nourishment. His humility is not just a moral lesson; it is a Eucharistic offering. He makes himself small, weak, and accessible so that he can be received, consumed, and become one with us.

As we contemplate Jesus offering himself as our food, the figure of Joseph becomes even more significant. The tabernacle key of some chapels and churches has a medal attached to it that reads: Ite ad Joseph—"Go to Joseph"—(Genesis 41:55). This phrase, which refers in reality to Joseph the son of Jacob, has popularly been applied to Joseph the husband of Mary. Like the Old Testament Joseph, who fed the entire nation from his storehouses, the New Testament Joseph also gives us food. Yet he nourishes us not with grain, but with the Bread of Life itself, with Jesus, the one whom he protected and raised.

***

Ultimately, contemplating the crèche is far more than an act of historical remembrance. It is an act that, as the liturgy teaches, unites all three "advents" or comings of Christ. In the manger, we see his first coming in the flesh of history. In the child laid in a feeding trough in the "House of Bread," we receive his third coming in grace, which happens now in the Eucharist. And by adoring this "King of peace," we prepare our hearts for his second and final coming in glory, when we may, as the Christmas prayer says, "merit to face him confidently when he comes again as our Judge."

"For he is our peace; in his flesh he has made both groups into one and has broken down the dividing wall, that is, the hostility between us" (Ephesians 2:14).

See Origen, Commentary on the Gospel of John, Book X, Chapter 18.

ST II-II, q. 29, a. 1.

The Roman Missal (2011), Collect of the Vigil of Christmas: "O God, who gladden us year by year as we wait in hope for our redemption, grant that, just as we joyfully welcome your Only Begotten Son as our Redeemer, we may also merit to face him confidently when he comes again as our Judge. Who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, God, for ever and ever."